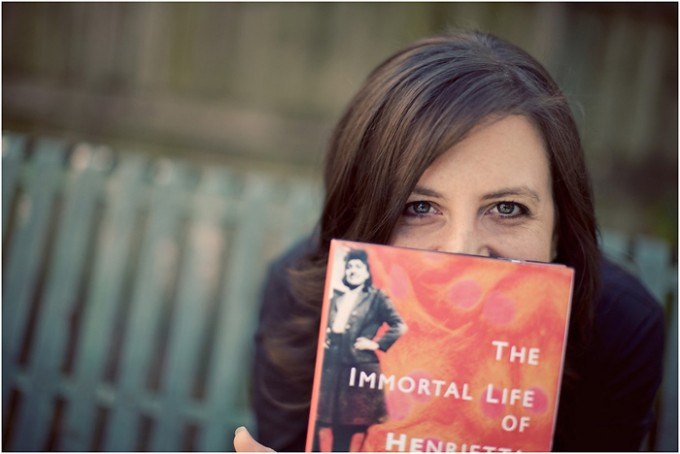

It’s a rare book that connects the reader to both the subject and the author, but that is the case with The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. As I added Rebecca Skloot’s name to my 2012 Book List, I realized that unlike most of the authors I read, I knew a great deal about her. It’s one of the reasons that The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is a compelling read.

The other reason, of course, is that the tragic yet very human story of Henrietta and her descendents cannot be put down and is rarely very far out of the reader’s consciousness. I’m a Gray’s Anatomy watcher — I’m behind right now, though, so don’t tell me — and I love medical dramas, but I’ve never even thought to ask what happens to all that blood and pieces of tissue that have been taken from me in the course of tests and hospitalizations. I just assumed that it was thrown away after a proscribed point in time. Apparently I was wrong.

When young science journalist Rebecca Skloot stumbled on a story about the source of the cells originally harvested from a cancer victim in 1951, she became part of the story herself. She spent ten years investigating the life and death of Henrietta Lacks, whose malignant cervical cells became the incredibly productive HeLa line used for tissue culturing in medical research. The world owes Henrietta Lacks a great deal, as her cells have been used for many medical discoveries, including the vaccine for polio.

Unfortunately, in 1951, indigent African-Americans being treated in clinics were not asked if they gave consent for much of anything, and Johns Hopkins doctors were no different from the rest of the segregated world in which Lacks and her family lived. Skloot has detailed a story of hope and wonder, as researchers at Johns Hopkins found that Lacks’s cells multiplied very quickly and remained viable in storage; they could be used and regenerated over and over again, something that scientists had not been able to depend on previously. The story also tells of a family devastated by the early death of a mother and the years of bereavement and poverty that followed. The obvious question becomes whether or not the Lacks family deserves to be compensated for the booming business that has emerged from Henrietta Lacks’s cells. Skloot leaves the reader to decide for herself.

Because Henrietta’s story and Rebecca Skloot’s story are intertwined, it’s amazing that Skloot was able to stay impartial and fair in presenting the Lacks family’s tragic tale. The book reads like fiction, but the science is also reported in an accessible and accurate way so that the reader understands both the human and the scientific sides of the issues involved.

I am really looking forward to talking about this book at Book Club next week, and I highly recommend it. I listened to it on audiobook and felt that the reader, Cassandra Campbell, was very successful in voicing both Skloot’s youthful enthusiasm and the Lacks family’s southern drawl. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is one of those thought-provoking, not-to-be-missed books — there’s a reason everyone is talking about it.